South Africa’s energy landscape is undergoing a period of momentous change. Not only is the country facing significant challenges in maintaining an affordable and secure supply of electricity while transitioning to net zero, it is also facing an imminent crisis in gas supply.

Join us for an in-depth discussion on this critical issue at our upcoming webinar on 6 August 2024

For the past twenty years, South Africa has relied on supply of natural gas from southern Mozambique for its chemical feedstock and energy requirements. The inland provinces of Mpumalanga, Gauteng and the Free State in South Africa have been receiving ~160 petajoules per annum (PJ/a) of natural gas from southern Mozambique. In addition, Sasol has supplied ~27 PJ/a of Methane Rich Gas (MRG) from its’ Secunda facility to various customers in Mpumalanga and KwaZulu Natal.

This gas has provided South Africa with an ultra-reliable, low cost and environmentally friendly energy and industrial feedstock for two decades. Unfortunately, however, production from these gas fields in southern Mozambique, operated by Sasol, is due to decline somewhere between 2026 and 2028. As a result, there are already indications that Sasol will have to withdraw supply of gas to its customers.

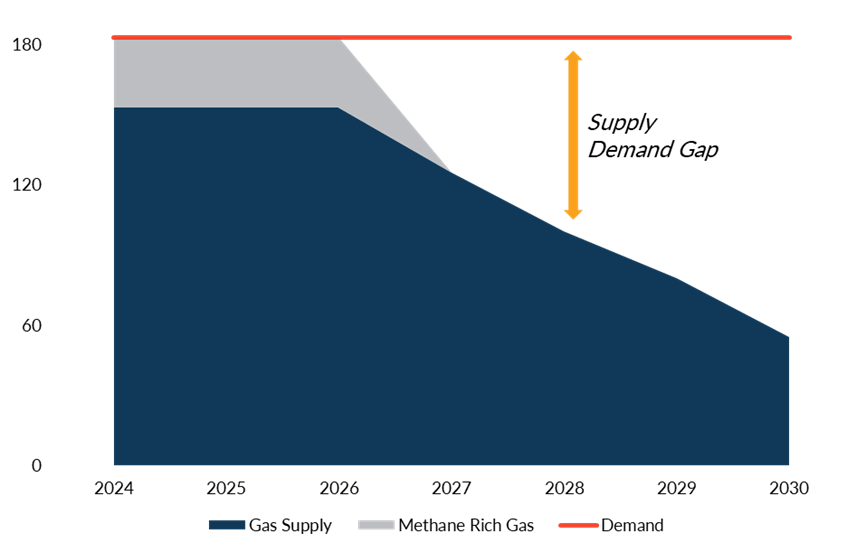

A widening gap between supply and demand for gas in South Africa

Therefore, South Africa needs to secure alternative gas supply for ~60-70PJ/a of gas, perhaps as early as 2026. In the longer term the country needs to secure a further 120 PJ/a of gas to replace gas supply to the petrochemical facilities at Secunda and Sasolburg.

The gap between the current demand for natural gas and its supply is shown in Figure 1 below.

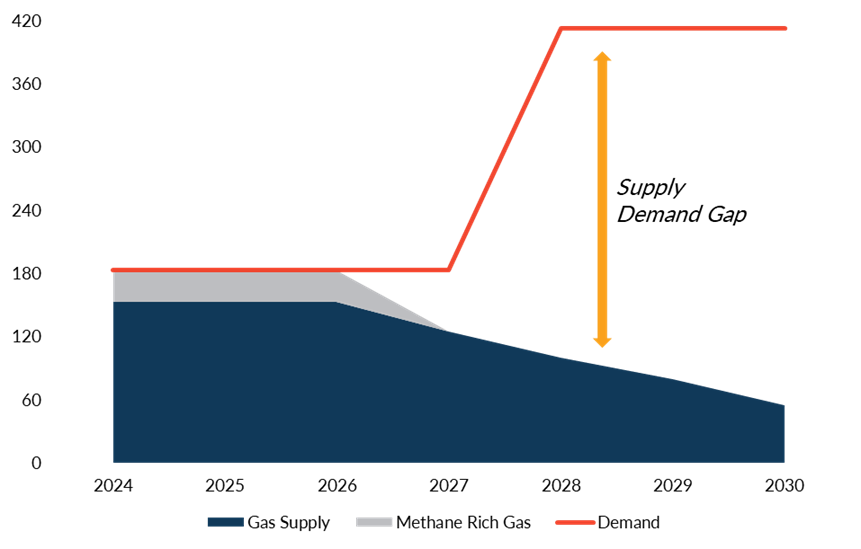

The looming gas demand-supply gap, and the challenges this poses, is made more acute by the emerging requirement for gas in power generation.

The recent improvement in the performance of Eskom’s coal fleet notwithstanding, South Africa faces great uncertainty regarding the long-term performance of its coal-fired power stations. In addition, there is the requirement for these coal-fired power stations to be progressively de-commissioned. As this de-commissioning occurs, the country is likely to become ever more reliant on a growing proportion of variable renewables and storage for its power requirements.

As the power grid becomes more reliant on renewables, it is likely that the electricity grid will require a substantial volume of natural gas to ensure stability. The IRP 2023 has forecast that 8,5 GW of gas-to-power will be required. In AIA’s own modelling of the power system, we found a similar requirement for gas-to-power. We believe that the country will require approximately 200 PJ/a of additional gas by 2030 to ensure adequate gas supply to meet the requirements of gas-to-power and ultimately security of electricity supply.

Taking account of both the need to replace the current gas supply from southern Mozambique and ensure that sufficient supply exists to meet the needs of South Africa’s industrial and electricity requirements, South Africa will require somewhere between 260 PJ/a and 400 PJ/a of new gas supply by 2030. This is illustrated in Figure 2 below.

How can this gas supply be secured?

There are two potential sources of new supply:

- Domestic and regional supplies of pipeline gas

- Imported LNG

South Africa has historically had very limited domestic supplies of natural gas, with the only operating gas fields being Block 9 in the Bredasdorp basin in Mossel Bay. Consequently, South Africa has had to rely on imported gas for its requirements.

This lack of domestic gas resource is however beginning to change.

Firstly, the recent discovery of gas in the Outeniqua basin by Total has created the prospect of significant domestic natural gas supply for the southern and western Cape. This resource can provide a significant source of gas supply for power generation as well as commercial and industrial markets in the Western Cape. In addition, developments of gas fields close to Virginia in the Free State (comprising both helium and methane) as well as promising discoveries in Mpumalanga hold out the prospect for exciting on shore gas development.

The biggest opportunity, however, remains the potential for large discoveries of oil and gas off the West Coast of South Africa, in the Orange Basin in particular. Discoveries over the last two years in Namibia have positioned the Orange basin as one of the most important emerging hydrocarbons basins in the world. Hence, there is a real prospect that South Africa could see very substantial hydrocarbon discoveries over the coming decade within its territorial waters.

Regionally, outside of Namibia, there have also been very substantial gas discoveries, particularly in northern Mozambique.

While all these discoveries create very substantial opportunity for domestic and regional gas supply in South Africa, several challenges need to first be overcome before this potential can be realised.

Large gas resources such as Rovuma are a long distance from South Africa and are therefore not suitable to provide pipeline gas supply to South Africa. Similarly, potential hydrocarbon discoveries off the west coast of South Africa will require very substantial investment in pipeline infrastructure to meet the needs of South Africa’s industrial users in the eastern parts of the country.

Finally, the timing of these gas discoveries represents a key challenge as it is highly unlikely that the gas from domestic or regional resources will be available in time to replace supply from Mozambique. It is critical that South Africa therefore finds an alternative source of supply to bridge the gap as we seek to develop our very significant hydrocarbon potential.

Bridging the gap through LNG supply

Given the urgency of ensuring adequate gas supply to the eastern part of South Africa, the country has no alternative but to facilitate the importation of LNG. While the timelines for the development of some domestic gas resources sits between 5 and ten years, and LNG terminal (assuming we start soon) can be delivered within the next four years.

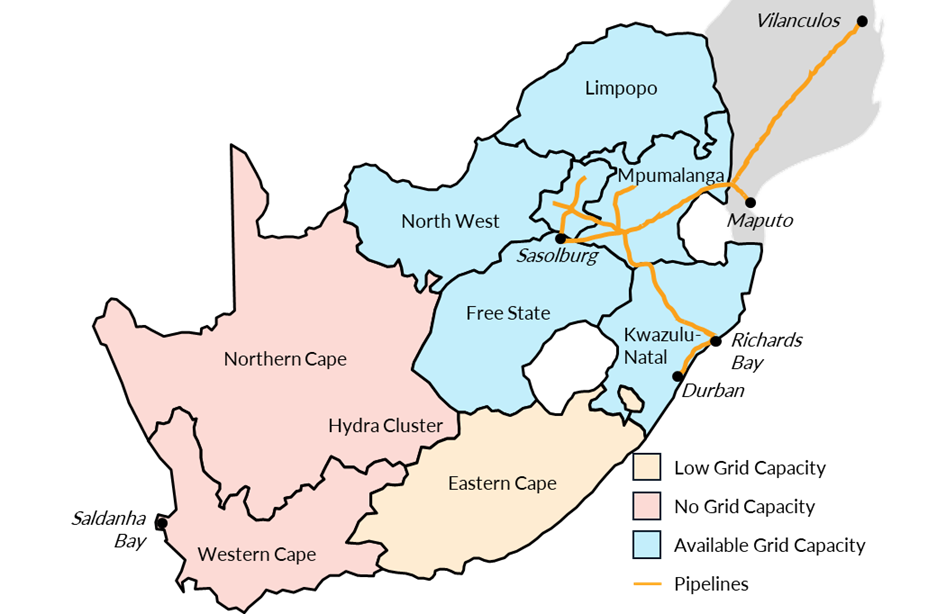

A key question is where such a terminal should be located. In doing so, one must start by considering the location of South Africa’s existing gas consuming industries, gas pipeline and electricity grid infrastructure. This is shown in the mape in Figure 3 below.

From the above map it is evident that the harbours of Maputo and Richards Bay provide the most suitable locations for LNG importation and supply in light of their proximity to existing gas pipeline and available power grid infrastructure. While the ports of Nqura and Saldanha Bay for instance provide further options for LNG import they are not feasible supply options for the eastern industrial hubs of South Africa.

It is critical therefore that LNG development at the ports of Maputo and Ruchards Bay are progressed as a matter of urgency.

The key question therefore is how we ensure that both the import of LNG and domestic gas production is enabled timeously to ensure South Africa realises the full potential of its industrial potential and domestic gas resources.

A practical way forward

Ensuring adequate, economic and timeous supply of natural gas requires an agreed roadmap of actions between government and all private sector stakeholders. In our view, such a roadmap should address the following four critical areas to ensure that the full potential of natural gas in the country’s energy mix is realised:

- Ensure that gas supply to South Africa’s existing gas users is maintained at the most economic price;

- Promote the development of gas production and importation infrastructure in markets that have not historically had access to natural gas supply;

- Ensure that South Africa is able to meet the requirements for gas-to-power in light of the longer-term uncertainties regarding electricity supply;

- Facilitate the development of South Africa’s upstream potential in line with the country’s climate change and energy transition commitments.

To do this, we think that the country should prioritise five key short-term actions as a matter of urgency while working on its key longer-term initiatives to build its gas economy.

1. Ensure that existing pipeline gas supply from southern Mozambique is extended for as long as possible to ensure the country can buy time to secure alternatives;

We believe that options do exist to extend the supply of gas from southern Mozambique beyond 2026. This can be done through further investment and exploration in the southern Mozambique gas fields. It will be critical that regulators, customers and producers engage to find a fair and equitable formula for such investment to be made and gas supply beyond 2026 to be enabled.

2. Re-frame the current GASIPPP RFP to ensure that sufficient offtake volume is secured to support the investment in LNG import infrastructure at Richards Bay and Matola required. This in turn will be necessary to ensure affordable LNG supply for power generation;

As discussed above, it is critical that South Africa secure LNG to firstly address the shortfall in gas supply to current gas users and secondly ensure adequate gas supply for power generation.

To do this, sufficient concentrated demand needs to be created to justify the large investment in infrastructure. Typically, an LNG facility requires gas demand of ~100 PJ/a to justify the investment in logistics and regassification required. This is roughly equivalent to the demand from a 2-3 GW gas-to-power facility operating at ~60-80% load factor.

Unfortunately, the current GASIPP RFP seeks to split the procurement of gas-to-power between different locations and effectively restrict the capacity in any one location to 1000 MWs. This, together with the specified load factor, would limit the offtake from gas-to-power to no more than 20-30 PJ/a which is well short of the volume of gas required for an LNG terminal.

It would therefore be important to reframe the RFP to maximise the gas volumes that can be purchased in any one location given the power requirements.

3. Broaden the scope of the GASIPPP RFP to include projects within the region and not just South Africa;

Currently the Independent Power Producer programme precludes participation by producers outside of South Africa. Once again, given the need for scale for LNG importation and the critical role gas-to-power needs to play to enable such scale, we believe that allowing LNG and gas-to-power facilities in Maputo to compete in the SA GASIPP programme is critical to enable timeous supply from Maputo. This in turn will be very necessary to provide the country with options for continued gas supply to the inland of South Africa.

4. Facilitate the development of onshore gas resources near South Africa’s eastern industrial base;

South Africa has a well-developed framework to ensure that the country’s mineral and hydrocarbon resources are developed in line with the constitution. In practice, however, the different regulatory requirements to develop these resources, often governed by different government agencies, can slow down development.

To speed up regulatory approvals, while ensuring the sector remains well-regulated we believe that provincial and national governments should establish regulatory “one-stop-shops”. These can facilitate a well-co-ordinated approval process that can ensure that unnecessary delays in the required regulatory approvals are not experienced.

While this will not obviate the need for imported LNG for South Africa to bridge its gas supply gap, enabling economic domestic gas supply can make a significant contribution to diversifying the country’s energy resources and providing much needed economic development.

5. Enable the development of the discovered gas resources in the Outeniqua basin off the southern Cape coast;

Finally, the discovery of substantial volumes of gas in the Outeniqua basin has created the opportunity to develop gas-to-power capacity in the southern Cape and also ensure natural gas supply in the Western Cape, utilising domestic gas resources.

According to our estimates, the gas from these fields could support a 1,4 GW gas-to-power facility at Mossel Bay and provide gas supply to industrial and commercial customers in the Western Cape.

Given development timelines, we expect that such a 1,4GW gas-to-power would be available by 2030 and would be a good deal cheaper than imported LNG. We believe therefore that the development of a Mossel Bay gas-to-power facility, utilising gas from the Outeniqua basin, should be a key national priority. To enable this opportunity will however involve Eskom, PetroSA and key national and Western Cape government entities. It may also be necessary to appoint an aggregator to enable industrial and commercial gas supply in the southern and Western Cape.

We believe that the above short-term actions are critical to ensure energy security, both gas and electricity, between now and 2030. They are however not sufficient to fully exploit the benefit that can be derived from South Africa’s hydrocarbon potential.

Over the longer term we believe that South Africa should define an energy strategy and policy that provides a decisive roadmap that firstly enables the development of South Africa’s upstream oil and gas resources and secondly integrates this into the country’s critical energy transition. To be able to effectively do this, South Africa’s energy strategy needs to address the following:

- Ensure that South Africa’s regulatory infrastructure can efficiently facilitate the development of South Africa’s West Coast upstream resources in line with our constitution and oil and gas legislation. This would include the implementation of the “one-stop-shop” regulatory approach outlined above;

- Provide a basis for potential oil and gas producers to understand, forecast and plan for long term gas demand in South Africa to de-risk gas production;

- Develop an integrated infrastructure development plan incorporating the development of upstream oil and gas resources off the west coast of South Africa with the development of the Northern and Western Cape’s renewable and green hydrogen resources. We believe that such integrated planning can ensure that hydrocarbon development off the west coast of South Africa can enable the infrastructure such as pipelines and gas turbines that can in turn be utilised for the utilisation of green hydrogen.

- Ensuring that South Africa’s upstream licensing and regulatory regime is on par with global standards to minimise ghg emissions from upstream oil & gas production. This will include trying to maximise the integration of renewable energy and also reducing methane leaks and flaring to a minimum.

- Invest in research and development efforts around CCUS to enable continued use of gas in a net zero world.

We believe that undertaking the above actions in a structured, deliberate and programmatic way can firstly ensure South Africa’s energy security in the short term and secondly facilitate long term economic development.

This will however require a concerted programme of action, similar to that undertaken to address the electricity and logistics crises. As with the other challenges the country faces, no one person or institution has all the answers and so it will require co-operation across multiple stakeholders. However, with such co-operation, natural gas can play a critical role in South Africa’s economic development and energy transition.

Jul 2024 Gas Southern Africa Energy Electricity Regional Gas Masterplan