With the future of South African electricity generation increasingly being discussed, AIA asks whether all the available technologies are being given equal consideration. AIA has worked on projects with major industry players in South Africa’s gas and coal industry.

At COP 15, held in Copenhagen in 2009, South Africa committed to a 34% reduction in carbon emissions below the business-as-usual case by 2020, and a 42% reduction by 20254. While the Copenhagen Accord is not a legally binding agreement, it does provide an important indication of the government’s stance on climate change. It is in light of this that the continued reliance on coal-fired power, as evidenced by the on-going construction of the Medupi and Kusile coal-fired power stations, should be questioned.

In addition to Medupi and Kusile, the IRP2010 (Integrated Resource Plan 2010) makes provision for a further 6.2GW of coal-fired power capacity to be built by 2030, as well as 9.6GW of nuclear power capacity3. While nuclear power does not produce any direct carbon emissions, it does come at a considerable cost: According to the IRP 2010 this is ~R27k/kW of installed capacity, which is likely to be higher now. Some experts are predicting that South Africa’s planned nuclear programme will cost the country up to one trillion Rand5. This is all occurring in an environment of uncertainty with considerable confusion over government’s intentions on nuclear energy as conflicting signals have been given by various political leaders, officials and energy experts. Carbon emissions and capital costs are not the only variables in the equation. Due to South Africa’s dependence on coal for power generation, as well as the historically cheap nature of that coal, South African electricity had been highly competitive on a global level. The high cost of new coal and nuclear generation capacity, as well as increasing CO2 concerns, pose a threat to South African competitiveness. Add to this the proposed carbon tax, and it has to be asked whether or not the country would be able to attract significant investment in the form of large scale manufacturing plants or smelters when the electricity price is no longer competitive?

Sentiment for renewable energy being the way of the future is strong, but investing heavily in a renewable strategy at present brings to the fore a number of complications. Not only are the capital costs for renewables very high when compared to other forms of generation, but the efficiency of the available technologies have not yet reached a level where renewables can be relied upon to provide base load electricity. In order for renewables to have a higher load factor, and therefore be able to provide base load electricity, a viable and cost effective option for the storage of energy would need to be developed, as the current options are uneconomical. In addition to the above, the current scale of renewable generation is comparatively low, which is partly due to the high capital costs associated with it. A large and costly renewable build programme would merely compound the cost pressures and the loss of South African competitiveness. The question then is: How does South Africa ensure that the growing demand for electricity is met, while still reducing CO2 emissions in a cost effective way?

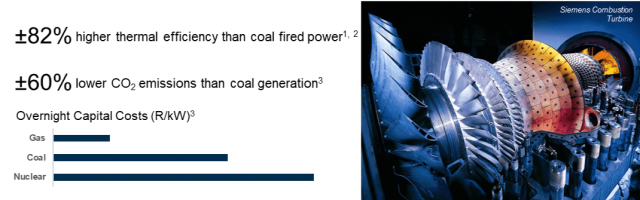

Gas-fired power generation offers a solution to many of the above problems. The thermal efficiency achieved by a coal-fired power plant, around 33%1, is significantly lower than the 60%+ achievable by a combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT)2. Although still a form of fossil fuel generation, CO2 emissions from gas electricity generation are approximately 2.5 times lower than that of coal generation3. At ~R6k/kW of installed capacity3, a CCGT plant demands a significantly lower investment compared to that of coal, nuclear or renewable forms of generation. CCGTs are also able to reach capacity factors of up to 85%6, thereby making gas-fired power generation a viable option for the supply of base load power. The combination of all the above factors means that gas electricity generation has the potential to rival nuclear and particularly coal generation in South Africa.

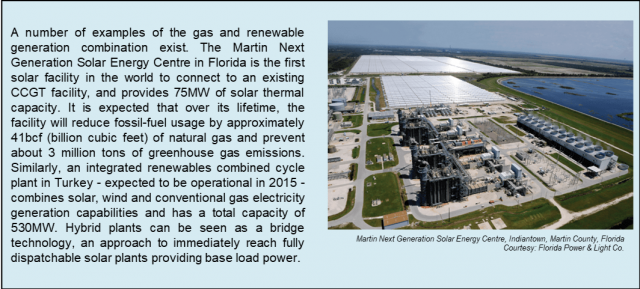

There is also an argument for combining gas and renewable generation. The intermittency and unpredictability of renewable power output may pose a challenge to grid stability, and as a result a flexible alternative would be required to compensate for this fluctuating availability of power from renewable energy sources. Gas electricity generation, with its highly versatile operating response, is ideally suited to be this alternative, and combining it with renewables would reduce the variability of supply, and the combination could therefore act as base load power. Pursuing a gas electricity generation strategy in South Africa does have some challenges associated with it, chief amongst which will be the securing of a sufficient supply of gas. There are, however, a number of options which could be pursued. In Mozambique, the Rovuma Basin is ranked as one of the most prolific conventional gas plays in the world, with an estimated 85 trillion cubic feet (tcf) already discovered and yet-to-find reserves of up to 80 tcf7. Other options include coal-bed methane

(CBM) reserves in Botswana, off-shore fields in Namibia, as well as shale gas deposits in the Karoo (although this would be a long-term project). The viability of LNG imports should also be considered. A major benefit associated with importing LNG is that the regasification plant and the CCGT could be placed in coastal areas where the grid is currently stressed, such as KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape. Similarly, gas from Mozambique can be transported via a pipeline down the coast to KwaZulu-Natal. In addition to securing a sufficient supply of gas, the infrastructural development to facilitate the use of gas will also be challenging. This would require a sustained effort from both the public and the private sector, in order to develop a robust gas market in South Africa for regional gas. Gas-to-Power in South Africa has broad regional implications. Developing the local gas market is likely to require development of Mozambican Gas together with a regional infrastructure network. The benefit of this is not only to South Africa, but to the Southern African region as a whole, providing a catalyst for economic growth as well as emissions reductions.

Oct 2020 gas power developing